Introduction

For a long time, I’ve been interested in the limits the modelling community place of modelling. It is often said to be about having fun, and perhaps because of how we associate it with a childhood hobby, and certainly as a hobby for all ages, there is a certain amount of peer-pressure, to “keep it light”. This manifests itself in person, but especially in social media, as a pressure to avoid anything too dark, and anything ‘political’. These two are big subjects on their own, so I have decided to split this blog post so as to avoid it being too long for most to read. Politics in modelling will follow soon.

Modelling the Darkness

Modelling the darker side of humanity is not as taboo as it once was. Around ten years ago, I can recall people being upset about the modelling of dead bodies and injury. Since then, the hobby has come to accept these, to a certain degree, but it remains fraught with challenges.

There is still a propensity to focus on engineering rather than a full picture of history. Modellers tell themselves that because they know how many quarts of oil you need to lube the transmission on an M4A2, or how many shots the barrel on a Tiger tank was good for, they are historians. To an extent that is true. They are very well informed on aspects of history, but they are very narrow in their field of knowledge and often know very little about the wider picture. That leads us to concentrate on the vehicle, or aircraft, or even a single figure and their uniform details, as the only real purpose of the model. Essentially, we model without context. We model the war machines, without modelling the war. Let’s not forget the business of war is to kill each other till one side can no longer tolerate its losses, but we don’t usually model the actual killing, only the men and machines that are employed in doing the act. But if we rarely model combat, we virtually never model the ‘crimes’ of war. But this too happens in every war in history, in some to an endemic or even to an industrial degree.

But if we think modelling can be an art form, or at least, more than just playing with toys, then why shouldn’t we tackle controversial subjects? Why shouldn’t we take on the darker side of war and humanity? Why shouldn’t we push our modelling, if we want to, so say more than “this is what this tank or plane or ship looked like”?

Let’s put a pin in why usually do not tackle these things, and have a look at a modeller who does

Rick Lawler and Burden of Sorrow

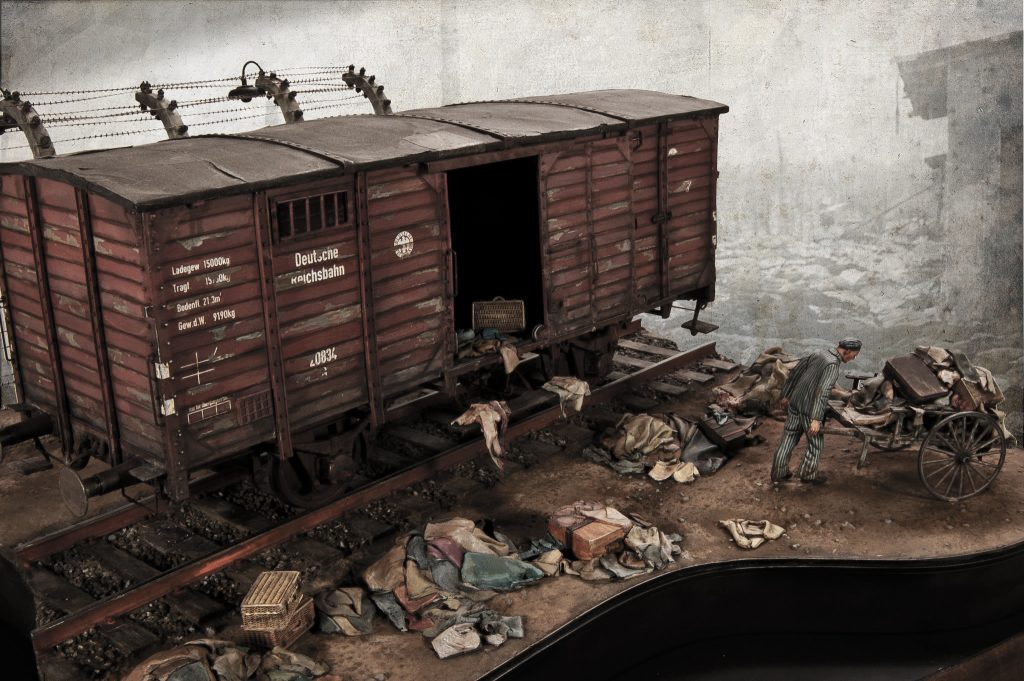

in 2013, Rick Lawler unveiled his new piece, “Burden of Sorrow”. It remains probably the best diorama or model I have ever seen, that addresses the Holocaust.

We recently Interviewed Rick about his more serious work on the Sprue Cutters Union and asked him about how that diorama came about:

Rick

“Burden of Sorrow in particular, was a very specific, emotional directed type of scene. So, I had the idea … of doing something around the Holocaust for some time, knowing full well that subject in and of itself is somewhat taboo. You just don’t go into certain sorts of subjects because they’re controversial, for lack of a better word. And I wasn’t necessarily ready to do it either…I went to the Smithsonian, to the Holocaust Museum and it was the second time I’d been there… This time I did it by myself, and that gave me the time to really be a part of the museum. ..and you go into that train car and then come out and then you have that smell, they have all these shoes behind this kind of plexiglass wall there and the entire place smells of old leather and old shoes.

That was the moment when I said, I need to figure out how to do something about this subject… So that became the motivation to… to figure out how to make this happen. Coincidentally, this is where this lightening in the bottle kind of concept starts coming through… So, that rail car [LZ Models resin German Rail Car] came out and all of a sudden it just coalesced. I knew what the scene was going to be now. The rail car was gonna be the center of the scene. It needed to be captured because I just walked through that rail car. And so it needed to capture that rail car and somehow capture the surroundings, the smells, the experience of walking through that museum and everything that goes around that museum and what it represents. So now I had a focal point, I had an idea, and now I can start making it come to fruition. But I couldn’t force that.”

Tracy

“Well, unlike a lot of dioramas and the stuff that we see even at the best shows… this is something that has to be handled with real sensitivity in order to be respectful and to convey what you’re trying to convey without being garish or flippant. And it’s a lot different… from a Tiger tank with a bunch of guys standing on it, pointing.”

Rick

“Yeah, and I was fully aware of all of that. Even back in the day, people would do, even start touching on sort of these subjects and it would roundly get criticism. “That’s gross, we don’t portray that in Scale modelling” I think the barriers have come down somewhat, but it was very much just about the model, like you said, Tracy, the tiger tank with the commander pointing and all that kind of stuff. But to actually tackle the realities of what our subjects often touch on, the brutality of it all, that was like that fourth dimension, that was that wall that no one really had approached before that.”

…..”You know, to say that I intentionally went to make Burden of Sorrow is not accurate. To say that it started with a base-level kind of, you know, back of my head, sort of an idea, theme, if you will. Then, like I said before, all these things started kind of accumulating until the time was right to actually express it in the modelling.”

Chris

…”You said that subjects like Burden of Sorrow are controversial. Why do you think they’re controversial in modelling? Because, something people always like to say whenever there’s any criticism thrown around about their panzers or whatever it is. “I’m just honoring history.” But quite a lot of the time, I think modeling sanitizes history. It shows a very non-violent, quite pacific, and quite attractive vision of war. Why do you think the darker side is so controversial?”

Rick

“Because it’s uncomfortable. I think it makes us take a look at ourselves and, perhaps question why we are attracted to, say, the glamorous side, you know? And so, you know, everybody loves a good tiger tank in a black Panzer uniform because they look really, really cool, but that level below that is not nearly so attractive. And so it’s, I think there’s a kind of a self-editing buffer someplace in there, which people just say, you know, we’re showing history in terms of the vehicle and the uniforms and this and that. Glamorize it for lack of a better word, but we don’t show the consequences. And that’s where Burden of Sorrow went, in a very deep way, to show the consequences of not just the Tiger Tank, but a regime, which takes it to a much broader scope. So, I don’t know, that’s my short answer, I guess. I also think that, its very difficult to portray, And I’ll use the term specifically, the horrors of war without being overt or grotesque in doing that. And that’s a very difficult line to follow in terms of being able to capture the essence of the scene to show the emotion to give, to tell the story without it just being a huge mess, aesthetically, physically, visually, not portrayed well, whatever, however you want to say that. So that’s the other challenge in terms of all that getting our own filters out of the way, in terms of how now do we actually do this? And that makes it much more tougher of a realm to push our modelling into.”

Rick’s “Burden of Sorrow” barely needs any introduction, it is arguably world famous, and rightly so. Of course, it’s a tour de force of actual modelling. There is not a single element which is not superbly executed (and trust me I can always find an element I think is not quite right) for me, modelling-wise, its probably as close to perfect as it gets. The composition is dynamic and original, the rendering of everything, from cloth, to metal, to wood, to the ground, is incredibly detailed, from the macro impression to the fine marks and micro colour shifts, and over colour palette is muted but verging in warm, which lifts it and gives it some vitality that a fully desaturated palette cannot give. This edgy of warmth stops the colours blending into each other too much and keeps tonal separations.

But of course, all of that is subconscious support to the wider point of the piece. What hits us is not the execution, it’s the emotion. It’s the story of the piece and the humans in it. The figure in the piece is not the only human, in fact I would argue the humans in the piece that hit us like an emotional bomb are the ones missing from it. The ones that left their possessions behind. What Rick has done is hit us with the absence of them, the essence of this crime against humanity.

As Rick said in our SCU interview:

Rick

“the biggest tool that we have as a modeler, as a presenter of our work, is actually the mind’s eye of the viewer… We don’t necessarily have to tell the entire story. We don’t have to put every detail out there. We have to start the paragraph and allow them to fill in the verse behind that” … “So you don’t have to be gross and gory and horrific in terms of what really happened there in terms of actually modeling that. You just have to kind of let them kind of, tell themselves that story and then they’ll fill in the blanks” …”This is I think was where we start getting into the art part of it. If that’s done well, if you’ve given them that little bit of a teaser at the beginning, each viewer is going to have a different experience. So when they look at that, you know, Chris will have one vision in his head and Will will have another vision in his head and Tracy will have another vision in his head and they will be unique but they’ll also be within the theme.”

In this case, Rick has handled this atrocity very carefully, and with great sensitivity, without lessening any of its power to shock and touch us, by leading us to the idea of the war crime without showing us the worst of the war crime.

SOME KIND OF MONSTER

A few years later, in 2020, Rick made another diorama, at the behest of Fernando and AK Interactive. This time he tackled the genocide of the Rwanda Civil War of 1994.

Rick

“This one was, prompted, let’s put it that way. Fernando, [ head of AK], he’d had in his mind to do a publication that was going to be about what he called ‘provocative subjects’. So kind of. as we were discussing before, subjects that would move the modeling world a little bit into that side of the direction, you know, create some buzz, some…controversy in a good way, some retrospect[sic], some thought. He had asked if he could use Burden of Sorrow, and of course I said yes, and he said, well, I’d like you to also do a new piece … for the book, and I just said, … I don’t know if I can do that, because…you know, to try to force something like that. I just said, I don’t know if I could do that because it was a special time, special place for that first one [Burden of Sorrow]. So he kept saying, you know, let’s give it a shot. Let’s try it. Let’s do this. And that lasted for literally about a year that he would say from time to time, hey, Rick, how are you doing with that project? And I would say, hey, Fernando, I don’t feel it…

So finally, we get to a point, like I said, about a year later, and he said, well, this book is going to happen, and I’d really like to have your contribution, a new piece from you. And we had that same back and forth, and he said, how about if we do something around Rwanda, the genocide in Rwanda? … I knew of it, but I wasn’t really versed into it, or anything like that. So he sent me some photographs… and says, what if you did a scene such as this? … They were of like front end loaders, like John Deeres and Hitachis or big construction equipment, basically scooping up bodies and clearing land that people had been basically slaughtered in and putting them into ditches, much the same as you would see in those Holocaust videos at the end of World War II. And I said, okay, I’ll do something. And I started actually down that exact path of what the photographs laid out. So I actually built a loader. It’s a Hasegawa, a little front-end loader. And once I got that finished, I started trying to conceptualize what the scene would look like. Because I still didn’t have it in my head what this was gonna look like when I got done with it. And it was at that point I’m going like, … this concept is not gonna work, at least for me… The loader was too large, which created the scene that was gonna be, the base was gonna be too large. I was gonna lose all the emotional impact of what this was gonna happen. It was gonna easily slip into that it’s too grotesque, just all these bodies, that kind of stuff.

“And I thought, I need to recalibrate this. So that led to what it ended up being, which was take the mechanical part out of this, which was, had this fellow who, you know, happens to have the task of having to bury these bodies and he’s just got his spade and he’s just like basically standing there in the scene, taking a break or reflecting on what he’s doing, this terrible task that he has to do.

and then this small child that’s above him, who is either like I mentioned, either his son who’s there just to help, or maybe he’s a child of one of the victims that’s in this trench. And that brought it back down to a very much more emotional and personal level that I think a viewer could empathize with.”

Again, Rick created a scene that relied more on the emotion of the witnesses, the gravedigger and the child, than it did on the death in the scene, although this time ‘bodies’ are present in the form of body bags. We know there is death here, but the emotion is in the two witnesses, not in blood or gore.

However, like Burden of Sorrow, it presents us with an aspect of war that people do not model. These are not cool looking tanks, they are not technical models of perfectly researched specific aircraft types. They confront us with what war is, and what its depths can descend to.

When it Isn’t Done Well

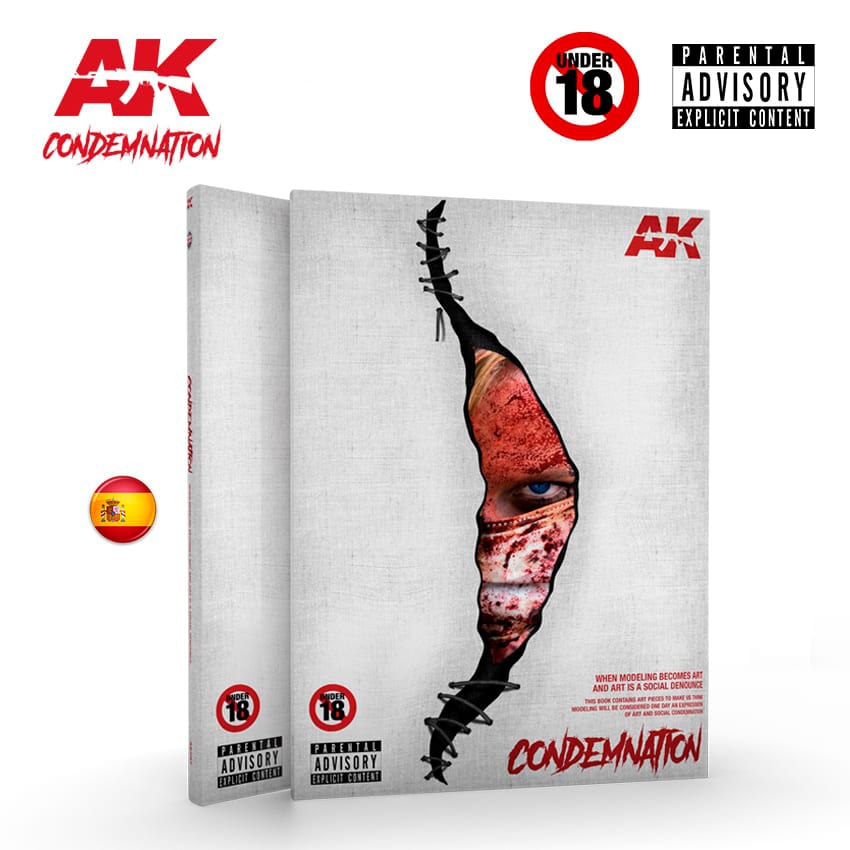

The book “Some Kind of Monster” was made for, was the now infamous book “Condemnation” from AK Interactive. I asked Rick about why this book became so controversial.

Chris

“… the book seems to have had very, I think, very laudable aims of trying to do what we’re talking about, of doing it and doing it well, but it wasn’t received very well. Why do you think that was?

Rick

“Well, I think it came down to just the initial marketing campaign. It was certainly off the mark. …As a contributor, I sent in my articles and again, this, this project had been going on for, for quite some time, I had no idea of the, when the release date was going to be. And I wake up in the morning and I check my emails and my Facebook and whatever, and it’s jam packed with a bunch of people who are very, very angry at me and wishing not very good things, which is like, what the heck just happened? You know? So I didn’t even know it was been released. I had no idea. I finally did see the clips. There was one initially, I think another one came out either a few hours or the next day. And. I was taken aback, personally, by the clips and the marketing because… I understood what the intention of the book was supposed to be, which was to ask these questions and to kind of push modeling in, like I said, a provocative direction showing the… not the greatest sides of life and humanity. What it came across as, was a Freddy Krueger sort of horror story promo because there were splatters of blood. There were red backgrounds. There was a bunch of…barbed wire crosses here and there, and it just, it literally was a horror movie promo versus a promotion for provocative works of art. And of course the subjects inside were difficult by intention and so you put those two overlapping each other and yeah, it took quite a hit. I contacted Fernando I think the next day and I said, listen, I understand what you’re trying to do here but you totally missed the mark on the marketing here. This is absolutely backfiring. You probably know that by now. So I ended up doing a rewrite of the entire book for him, for them, over the next couple of weeks. They pulled it. They pulled the marketing for sure. I don’t know if they pulled the book, but they pulled, basically, I got the book and he says, okay, Rick, go through it and you take out [or rewrite] everything that you think is controversial, especially the introductions, because AK had written introductions to most of the chapters. So even my work had a new introduction to it. So, I rewrote all those, because they were much more aggrandized in terms of the horror and the whatever. And so. I sent that back and then they came out with a second edition or new release a month or so later.”

Tracy

“Yeah, it also underlines how… if you’re going to broach these subjects in scale modeling, you really have to do so with some sensitivity, you know?”

Chris

“Some respect as well, I think.”

Rick

“Yeah. And that was an interesting, that was certainly interesting few days to a week right there because that turmoil did not go away very quickly… It was… fascinating. You hear these stories about teenage girls getting bullied on the internet and such like that and they do all these things. That was … the closest I’ve ever felt like, oh my gosh, this is actually a pretty real feeling that you get when people that you know, people that you’ve had conversations with, other modelers, people you respect and such, are just chastising you for being involved in that project. And I’m like… you know, I don’t know what to tell you here.”

Chris

“I think the aims of the book were laudable and in a way it’s a shame that it got mishandled and that it did because I think it is important that modelling covers these things and goes beyond the usual kind of tank on a plank and stuff and tries to ask the audience questions.”

Rick

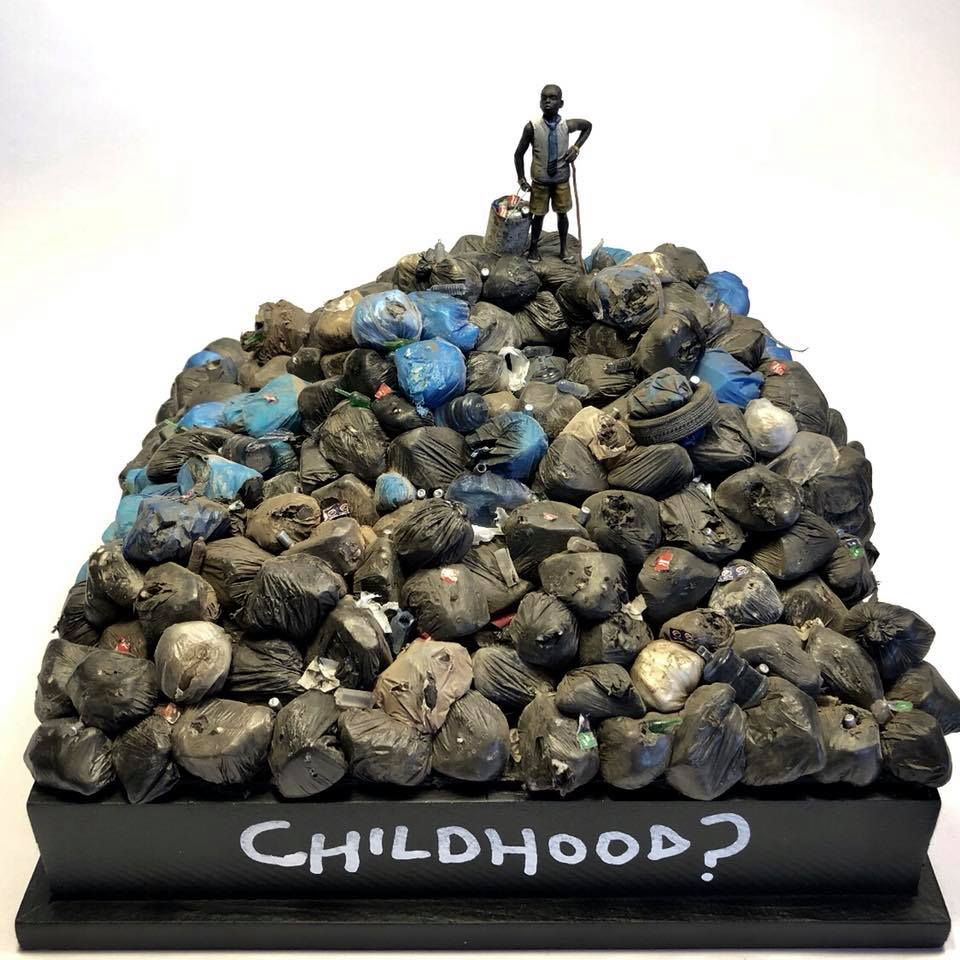

“Yeah, there’s some good pieces in there, in both editions actually, and including, and this is somebody that can be a very much part of this conversation that we’re having, is Pete Usher. His little boy sitting on top of those trash bags is part of the addendum of that book, or the gallery in the back of that book, which is a fantastic piece that, once again, communicates a very strong message.”

I very much agree with Rick that the marketing, and the sensationalisation of the subjects in the book were major mistakes that AK made in tackling such sensitive, but ultimately important topics. The vast majority of the content was very sensitively handled, and the marketing undid the subtlety of that.

But also, some of the content was, for me, problematic. In particular, the gas chamber diorama. In most cases the book was treated in the same way as any other AK book, and was largely a step-by-step book, and for me, colour call outs for gas chamber tiles, was a level of banality that jarred in a very distasteful way, with the subject of the model. If we are to consider works like this, as art, which they can be, I think we should be focussing on the subject, not the execution. The inference that we are encouraging people to copy these pieces is, at best, strange.

As Rick says, the book was re-edited and reprinted, at (no doubt) considerable cost and loss to AK. It is a fact in publishing that you have to sell a very significant proportion of a print run to even break even, and the way the second edition followed the first so closely, suggests to me that a large part of the first print run was probably pulped.

Although the first edition missed the mark so terribly, the ideal of the book is, in my opinion, noble. To make a statement about the darker side of humanity, and to try to use modelling, in the same way as art, to tackle these subjects. It is notable that in all the furore over the book though, that anger at the way the content was handled, and the marketing of the book, crossed over significantly with a subsection of anger that these subjects were even tackled at all by modellers.

What Modelling Can Do and What it Should Not Do

The reaction to the book is seen as being one thing, but really it was different kinds of complaints that merged into one reaction and dare I say, some of those complaints are the kind of reactions that I discussed at the start of this piece, that modelling should not address things like war crimes. I think that opinion is wrong. Pieces like Burden of Sorrow, and Some Kind of Monster, and Peter Usher’s ‘Childhood?’ are important models. Modelling can have a social conscience, it can ‘say’ something, and a culture that represses that is a culture that seeks to prevent modelling being something more than making scale representations of a vehicle, accurately built, and adequately finished, and I don’t want to work in a hobby that chooses to limit itself that way.

On the other hand, the legitimate criticisms of the book are fundamentally true. They go against what makes work like Rick’s and others so powerful: the understatement, the inference rather than the gratuitous show. The subtlety that focusses on emotion and not shock. If we are going to elevate modelling through addressing such serious subjects well, then we have a responsibility to do it with a huge amount of introspection and thought, and a sensitivity and subtlety that allows is to leave nothing out emotionally, while avoiding gratuitous detail.

Chris,

A very thoughtful, and thought-provoking post (and SCU episode). I just finished it this morning on my drive in to work (I wish I had known it was the last for the year, I might have saved it back. 😉 ) I’m still digesting it. It may be a bit before I’m done with it.

For the moment though, I thought I’d share a thought regarding the modeling of “objects” as opposed to modeling for a diorama. (And I’m not arguing that one is better/worse than another.)

For the better part of thirty years I participated in living history programs at historic sites, battlefields, museums, etc. both as an avocation, and sometimes as a vocation. Interestingly enough I recently read an op-ed piece by a National Park Service ranger on the purpose and role of interpreting details as they relate to the whole to give a park visitor a better understanding of the site and how it fits into history. I’ll try to make this as short as possible. Promise.

When a visitor attended one of my presentation or program, they truly didn’t care about the minute details of my musket, the material of my socks, or the cut and pattern of my jacket and coat. However, I could bring all of these things to bear in my talk if I could show how these little things reflected a society and a time that resulted in that person being there, along with thousands of other similarly (or not) equipped, and how this was both a reflection on the society it represented, and how it affected the outcome of the event being discussed. I think that can also apply to modeling an object (tank, plane, boat, car, etc.)

My also mind goes back to a senior topics in history course I took decades ago on the war in the Pacific. My professor, Dr. Muir, pointed out to the class how our examination of something like a U.S. aircraft carrier serves as an example of a society’s wealth, engineering, military philosophy, etc. Again, something that can be applied to modeling an object.

Apologies for the ramble as I’m firing this off quickly during my lunch break.

I wish I could remember the title, I’ve tried to find it, there is a book about rifles of WWII which uses them as a lens to show how they are the products of the societies that used them, in political, economic and philosophical (in terms of military philosophy of the infantryman and how he should fight) terms.

However, you need to have a very wide understanding of the overall historical context to understand that beyond a couple of headline factoids

yeah, ah.. This is difficult to deal with.

The horrors of war are sanitised by our hobby. It is when confronting models or dioramas pop up that we gain an insight into the horror.

The AK book appalled me for the reasons you have given. The idea of colour call outs just repelled me.

Well done work though is important to see. It has to elicit a visceral reaction in me for me to know that it is effective and not just red on a figure with a body part missing.

Burden of Sorrow gave me such a reaction when I first saw it.

I really feel like that book is maligned beyond its flaws. Certainly the call outs etc were repugnant, but for me the failure was one of editing. It could have been an incredibly powerful confrontation to all the cosy, safe depictions of war in modelling, but they screwed it. At the same time though, I feel like some of the critics would still have hated it, if it had been done well, just because it was confronting their concept of military modelling

“Burden of Sorrow” may be the most perfect diorama I have ever seen, for all the reasons you noted in your essay. It is the perfect balance of place and time, and because it does not show so much, it tells a much more important and deeper story than a stark depiction of the Holocaust in lesser hands. The depiction of the darker side of war and human atrocities has always been controversial, but they do exist and are part of the whole. Rick Lawler has shown us a story half-implied, yet complete. It is in its own milieu, magnificent…..

I am reminded of the closing scene in Stanley Kramer’s “Judgment at Nuremburg”….. Convicted Nazi judge Ernst Janning is visited by Chief Prosecutor Dan Haywood.

Janning: “Those people, all those people – you must believe me, you must. We never knew it would come to all this.”

Haywood: “The very first time you sentenced a man to death you knew to be innocent, it came to all this.”

sobering stuff indeed Bruce

Chris, Tracy & Will. Thank you for spending your time with me in our discussion regarding BOS, Some Kind of Monster, and the larger topics on the Sprue Cutters Union podcast. To be honest, I am amazed and humbled that Burden of Sorrow, and to a lesser extent my other works are still talked about, and appreciated years later.

I certainly enjoyed our discussion, and cherish our friendships.

Take care,

Rick

I really would love to do it again sometime Rick, or work together on something, if you happen to find lightning in your bottle again.

Another thoughtful episode and discussion.

I’ve been thinking about the damage that a .50 calibre round can do to the human body. Are we ready for that kind of modelling that illustrates that?

that’s kind of the opposite of what I was saying I think. The damage a .50 cal round can do to a human is in the loss of the human for me. not showing the catastrophic mutilation

Very interesting take Chris- I’d also point people to artists who have used models like Jake and Dinos Chapman to make extremely vivid, and always controversial, artistic works.

I’d also suggest that what most modellers are isn’t historians as such, but more antiquaries of machinery. There’s nothing wrong with that either it’s just different. But it does explain why there can be an ability to separate the tools of war from their appliance.

— well to me anyway.

“There’s nothing wrong with that either it’s just different. ” Absolutely, but I think modellers could benefit from a wider understanding of history. I see a lot of urban myths repeated in discussions between modellers. But some people just want to build cool looking stuff and that’s equally valid. To be honest its how I approach modelling aircraft myself!

I really should have covered Jake and Dinos. I wrongly assumed most people wouldn’t know about that and I was leary of making this about art again, but you are one of many that have brought them up, which suggests I should not have omitted them.

I found that teaser video of AK, or part of it, and I didn’t find it upsetting at all. Quite normal for advertising a book of such content. Maybe I don’t live in the microworld of competitive modellers who thing that a diorama about holocaust is a political statement where presenting a particular Tiger or Panther of a particular commander, say Michael Wittmann, is not a political statement. Well, it is.

Also I haven’t found controversial at all Condemnation book. On the opposite, the topics of the dioramas were as mainstream as they can get, the kind of topics a multinational company would have in a social responsibility campaign. Controversial or shocking topics are something else, at least in my mindset.

However, it was a very nice effort to show to modellers and especially dioramists that you can do much more than is currently done. I’ve bought that book (revisited edition) for a friend who works in Africa for the UN and has recently developed an interest in dioramas. He really enjoyed it. I haven’t yet bought a copy for me, but maybe I will.

I really wonder what were the differences between the first and the revisited edition, but I guess I can find only the second.